Riptuk (Aquila Vulpes Ornithorhynchus)

Riptuk (Aquila Vulpes Ornithorhynchus)Conservation Status: ENDANGERED

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Verbrata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Monotremata

Family: Ornithorhynchidae

Genus: Vulpes Ornithorhynchus

Species: Aquila Vulpes Ornithorhynchus

DESCRIPTION

A Riptuk's farley.

A thought to be mythical species, Riptuk’s are brand new in the spotlight of animal species and are only found on one island on earth that was also thought to not exist called Euriteek. Riptuks (Aquila Vulpes Ornithorhynchus) weigh from 15 to 30 pounds (6.8-13.6 kg) Very large Riptuks can weight up to 37 pounds. (16.7kg). The adult Riptuk has a length of around 23-28 inches (58.4-55.9 cm) with a tail of around 16-22 inches. (40.6-55.9 cm). A Riptuk’s trotting stride is about 27-32 inches (68.6-81.3cm) long. Sexual Dimorphism is visible in the Riptuk species, males are anywhere from 5-10 pounds (2.3-4.5 kg) heavier than females.

Differences between males and females. Scent glands are colored in green.

Probably the most noticeable difference is the pea-like shapes that rest on the male’s tail, called pods, that are used for attracting females and marking territory. Scent glands are located on these pods, on cheek fur, and also in the black soft skin between the top half of the beak and the skull, where the nostril holes are located. This is called their farley. Females obviously do not have pods, but they use their tails also when marking territory. Riptuks’ have a very acute sense of smell used to locate prey and to find fallen fruit etc. The smell by using their beak like we use our noses but when they need an even greater scent range they open their beaks to expose the soft pallet that acts like a “jacobson’s organ” in cats. When a scent hits this pallet, its sends messages to the brain regarding the scent of whatever it is they are smelling.

Riptuks have a seemingly limitless color range, the most common are red, blue and yellow but practically every color of the rainbow has been seen on a Riptuk in someplace or another. They also have sometimes very intricate patterns, but often they are just one color unless bred to create a unique design. Beaks are a golden color, but pearly beaks have been seen in some chicks. Healthy Riptuks have a short double coat and a fluffy, plump tail. Male’s shed their pods once every year during dry season, but unhealthy males will not. The cause of the pods dropping off is unknown. A sick Riptuk’s farley will diminish from jet black to dark grey, an easy indicator to other Riptuks as to who to stay away from. Chicks are born with a light brown farley, that turns black when they reach sexual maturity.

Eye color is also very wide in range, but the most common eye color is a light chocolate brown. Purple and blue eye colors are recessive while green, amber, gold and chocolate brown are most dominant. Pupils are large and oval to circular in shape. Riptuks eyesight is similar to eagles, they can see extremely well and also have the capability to see more colors than humans. Their night vision is also pretty good, but not as honed, as they are diurnal. (They are active during the day and sleep at night)

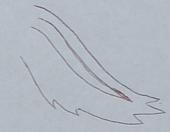

Riptuk tails are vital to every Riptuk. They are used as pillows and to shelter their young, kitsas, from the downpours of the rainforest. Male Riptuks have four pods on their tails that secrete a sap used for marking trees and for building dens. Besides being used as a scent marker they are used for fighting other Riptuk males during breeding season to win over females. These pods look like they might be squishy, but they are as hard as rocks. Males whip their tails at other Riptuk males in courtship fights. These blows can injure and possibly kill other Riptuks that get in the way. They are also used in the courtship dance explained in the Reproduction section. Male Riptuk tails are also the primary weapon used against predators. Raptors and other birds of prey are the Riptuks primary predators and one lash of a podded tail can easily break a wing.

The view of the Wetla from inside the tail.

Female Riptuks also use their tails for marking territory but instead of using the sappy substance of the pods an organ called a Wetla, runs through the tail that creates a powder that has a very potent scent. Swishing of the tail creates a fine dust behind a female Riptuk during breeding season, but off-season it is hardly noticeable to the eye, but still very aromatic to the nose.

DIETARY HABITS

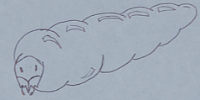

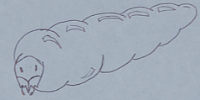

Warble Beetle Larva

.Riptuks are omnivorous and eat almost anything an everything. Their favorite food is Warble Beetle larva that can measure about 6 inches in length. They enjoy snacking on insects of any kind and another favorite treat is fruit with worms inside. They also hunt small rodents and bats by climbing trees and waiting for prey to pass underneath. They are also perfectly happy eating cocoa beans when other food is scarce. Living in the rainforest leaves plenty of prey for Riptuks to feast on. They typically eat 3-4 pounds of food each day during wet season and around 2-3 pounds of food during dry season.

Riptuck’s also enjoy fishing in the rainforests large rivers and swim frequently. When fishing Rip tuck’s use electrolocation, like their cousins the platypus, to find prey. They detect fish by senseing th e electric fields cause by muscle contractions. Their electroreceptors are located in their farley , which is why they dip their beaks underwater to many times during swimming. When looking for prey in the water they move their heads from side to side, to catch what direction the electric signals are coming from. Their eyes are closed when they go underwater, so they must rely completely on their electroreceptors to find underwater prey.

Electrolocation is also used to find bats in the thick, leafy branches of the trees in which they hide. Like fishing, when they enter the tree’s branches they move their heads from side to side to find prey.

Riptuks have retractable claws that are seemingly only used for hunting, marking territory, climbing and building dens. They don’t seem to realize that they could fight with them if the wanted to. Beaks are their primary hunting weapon, they knock prey from wherever it is sitting and then break its bones with a snap of the beak. Riptuks do not need to chew, making meals much faster to avoid attracting predators.

During the dry season, almost all unfinished meals are brought back to their dens and buried inside to be eaten later. This is most likely because prey is scarce in the dry season.

BEHAVIOR

A tree den.

Riptuks are a diurnal species, meaning they are active during the day and sleep by night; like humans. They live in small packs, called Parlas, of usually 2-4 breeding pairs that share a territory. Territories are generally very large and are only used during the wet season unless kitsas hatch late. They live in dens underneath trees. Technically they are burrows, but researchers have just decided to call them dens. The trees roots act as a defense system from predators that may try and dig them out during the night. A “den tree” is usually marked by the Riptuk’s clawing the bark off in a rig around the base of the tree, but it is unclear why they do this. Each pair of mates has a separate den if more than one pair live on a territory and the dens are usually in close proximity, usually only a few trees away form each other. One large den is in the center that is used for nesting and but when kitsas hatch they are moved back into their parent’s den until grown.

In each parla there are leaders who are usually the oldest breeding pair. In order to become leader, the lead pair must be beaten in a fight or die of old age. Leaders watch over the territory and regularly mark the borders with one or two other Riptuks. Lone Riptuks are rare because until kitsas find mates they usually live with their birth group and may even rejoin the parla after they’ve found a mate. Leaders seem to be the only class other than a parla member, there is no “underdog” of sorts.

Borders are marked by rubbing trees with cheeks and using their tails. Males wrap their tails around a tree in one swift motion, leaving four sap blotches that warn other Riptuks that this is their territory. Females are usually the border marking patrol however, as they merely have to swish their tails and shake of their powder.

A Riptuk screaming.

Riptuks are very stubborn creatures and do not give up their turf easily. When a rival parla attacks, which is very rare, Riptuks will go as far as killing to defend their homes, especially when kitsas are involved. First, the Riptuks being attacked and the attackers have, literally, a screaming match. These can go on for hours until a leader’s voice goes hoarse. Then the combat begins if one side hasn’t backed down. Tail and beaks are swung everywhere and usually each Riptuk picks one foe to attack, and leaders will take on the other leaders and any stragglers that don’t have a foe. Usually males fight males and females fight females and it is rare that once the combat stage is reached, that a Riptuk will escape unscathed. Males can have their necks broken by a swinging podded tail and beaks can be fatal if used correctly. If one leader dies, Riptuk’s seem to notice immediately, possible because of their electrolocation, and immediately submit by rolling onto their backs with tails between their legs. Perhaps this is because they do not want to risk their other leader dying, but it is unknown. If a leader feels that they will lose and kitsas may be killed, the will submit, but only by tucking their tails in between their legs.

Once a battle is over they gather up their kitsas and go to find new territory. If enough Riptucks die that some foes are still looking for a fight, they do not hesitate to raid nursery dens and kill any kitsas they find. And since they have electrolocation, there is no chance for any survivors.

Aside from fierce battles, Riptuks are very social creatures and often visit other territories surrounding theirs. When visiting a territory to visit, they bring along a piece of prey and any kitsas. These meetings strengthen relationships between parlas and help prevent battles. A greeting usually consists of a low growl noise and the two Riptuks rub cheeks. After greetings there is reason to suspect that Riptuks have their own language, as kitsas play with other kitsas the Riptuks sit around the play sessions and chirp to each other as if speaking.

A female Riptuk sheltering kitsas.

Female Riptuks have a very positive relationship with their kitsas and other Riptuks kitsas. They protect even unfamiliar kitsas from predators and will even adopt kitsa orphans. Male Riptuks will often only protect their parlas kitsas and will ignore strange kitsas unless visiting another parla. Male Riptuks usually teach male kitsas how to fight and hunt, whereas females will teach both genders.

COMMUNICATION

Riptuks communicate using visual and vocal signals. There is a suspected language of Riptuks but most likely it is in too low a frequency for humans to hear. Their tails and body language are another way of communicating, especially during breeding season.

Frequency is very important to Riptuks. Unlike most species, low frequencies are the highest form of praise and respect. Medium frequencies are used for talking and high frequencies are used for alarm.

Clucks are only used during breeding season, as well as the rapid beak snaps. Males are the only ones that use these calls, females usually sing during breeding season, but will also sing to calm kitsas.

Kitsas only really squeal and chirp until they are around 3 months old, when they start learning to “speak”.

Riptuks are incapable of human speech, but enjoy copying eagle screeches and leopard roars.

Body language is also very important, especially when Riptuks meet for the first time. Riptuks keep their heads up around newcomers and their tail drags behind them. They also do this when comfronting the leader of their parla. Sometimes male’s will puff out their mane of slightly longer fur that is usually hidden, especially if the new arrival is male. When meeting up with friends they rub cheeks once or twice and will brush them with their tails.

REPRODUCTION

The breeding season of Riptuks is a festival of color and sound, when all Riptuks gather together to embrace the creation of new life. In the last three weeks of the wet season male Riptuks travel from their territories to the rivers edge, where each male claims a tree, Riptuks mate for life, so it is important that they find the best possible mate. Trees are first come first serve and the most desirable are the trees on the water. Males will usually fight for the rights to a tree, because the best trees are where females look first for mates. When trees are established females and existing mating pairs arrive in a parade like fashion with breeding pair in front and females without mates in the back. When the females parade in, the males with cluck loudly, trying to stick out from all the other males. The females ignore their clucking and raise their heads high, dragging their fluffy tails behind them.

They settle on the receding banks of the river and dig burrows that house up to 8 Riptuks at a time. These become their dry season dens. It appears that established breeding pairs control breeding season, as they call the shots on when the females enter the forest to find a mate. While the females and breeding pairs are building burrows, the males are busy gathering leaves, fur, feathers and anything else they can find, and building large piles at the trees roots. This pile of “stuff: will eventually be the nests that house their eggs. Females are looking for the softest piles, because the softer they are, the warmer they will be for their eggs. Males also use their pod sap to coat the base of their tree, but it is unclear why, perhaps to appease the female’s nose as well.

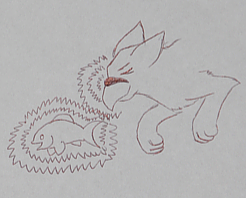

A male Riptuck's courtship dance.

When preparations are complete, the breeding pairs allow groups of females to enter the forest, in no apparent order. They are escorted by parla leaders of three parlas. As the walk through the forest females will leave the group to inspect nesting piles and try to find an acceptable mate. Males then do a breathtaking dance, they puff out their “mane” and bow, lifting their tail into the air. Then they begging to snap their beak together rapidly and hop up and down, shaking their manes. They bounce around the female in hopes she will notice them. Females can be encircled by dancing males, but if they begin to trap her in, parla leaders will break up the circles. Should a male stick out to a female, she will shake her tail at him, covering him with a powdery dust. Often females pick two or three males from the circle. When her picks are selected, the rest of the circle leaves. Then the female sits and sings a short tune. This seems to be the signal to begin fighting for her. Males viciously attack each other and the winner becomes the female’s lifelong mate.

Mates that have already been established do not go through this courtship dance. After the female’s mates have been selected, they swim across the river and dig their own burrows. Males and females build their nest together. Pairs that had kitsas the year before do not breed the next season, they care for kitsas that are still too young to breed.

EGGS

After breeding, females bring their mates back to their dry season den. The Males then go to work at building a nest from their pile contents. Females oversee the nest building process and will bite their mates if they think that they are building the nest wrong. It is unclear though how females know what the nest should be like. After the nest is built, females kick their mates from the burrow and the male retreats to his tree, where he live out the dry season. Males will hunt for their mates and their kitsas for the entire dry season, males with trees on the riverbank have the least distance to travel to get to prey and their kitsas and mates.

A newborn kitsa.

About a week after the courtship ritual, females lay a clutch of 3-5 leathery eggs. These aggs are usually gold with a hue that usually turns out to be the kitsas coloring, but offers no indication of its pattern. The female buries her eggs in nest material and then sits on top of them for about two weeks until they hatch. During this time period the male Riptuk hunts for his mate and in rare cases will starve himself to death to ensure she gets enough food.

When the eggs hatch, the kitsas are still very much undeveloped and this is the time in which most kitsas die. Mother Riptuks can sense when their kitsas hatch, but continue to sit on their nests. Kitsas do not need to be fed until they can make sounds, when their vocal chords develop and they eat their eggshells until then. Once a newborn kitsa strats to screech, the mother unburies it and sets it next to her belly, covering it with her tail. Riptuks do not feed their young with milk, instead they regurgitate food. If a kitsa dies because it does not develop fast enough and starves to death, the next time the male brings food he drops the dead kitsa into the river. Usually one kitsa in a clutch dies before the wet season starts.

An 8 week old kitsa.

At around 3 weeks of age, kitsas begin to walk, and always have their claws extended because they can’t yet retract them. Once they’ve mastered running and walking, at around 10 weeks of age, they are taught to swim and climb trees. Claws are now retractable. It is vital that kitsas learn to swim as quickly as possible, because bushfires could start at any time in the dry season.

At around 5 months kitsas learn to hunt and defend themselves, this process of training is focused on the most and training lasts until the next breeding season. At 7 months of age, when the wet season starts all of the Riptuks head back to their territories. This is very hard on kitsas and often they will climb onto their parents back to rest when the going gets too tough.

Kitsas become sexually mature at around a year and a half and are then considered adult Riptuks. Females usually become sexually mature earlier than males. Often if a kitsa becomes mature before breeding season, parla leaders will not permit them to breed.

CONGREGATION AND MIGRATION

Riptuks congregate once every year for breeding season and for dry season. During the last weeks of wet season the males depart and about a week after that, females and breeding pairs depart for the riverbeds. The Karan River is the only river used, probably because it is the deepest and longest river on the island. The Karan can get down to only about 3 feet (1 meter) deep in the worst dry seasons, but usually stops receding at about 15 feet (4.6 meters). Fish are the main source of food during this time, but in the end of dry season, Riptuks often have to resort to eating bark and feeding prey animals to kitsas.

They probably stay at the Karan River because it would be too dangerous to travel back to their territories with pregnant Riptuks. Some would not be able to get back before the eggs were laid.